100

There is a heuristic in discounting called “the rule of 100.”

When a product is priced at less than $100, the rule goes, it’s more effective to use a percentage-based discount; and when a product is priced at more than $100, it’s more effective to use a dollar-based discount.

The perceived value of the discount—even if a “percentage off” and “dollar off” offer net to the same value—flips, so to speak, when the cost of the product goes above $100.

For DTC, this is instructive.

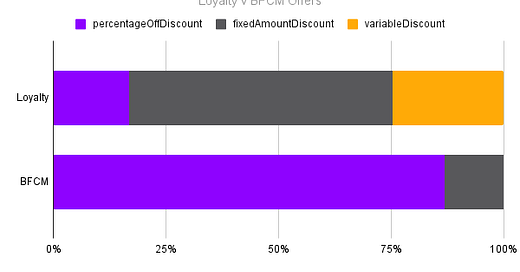

Since the vast majority of brands have an AOV of less than $100, the percentage-based discount is likely the right move. When we started analyzing loyalty programs, however, we found that 75% of loyalty programs leveraged fixed-dollar discounts.

Yet a hidden stat I found in our BFCM analysis is that, of the 500+ largest brands in our dataset, nearly 90% of them used percentage-based discounting for BFCM 2023.

Which poses the question: If brands are using percentage-based discounting for the most important sales season of the year, why aren’t they more willing to use it in their loyalty program?

In looking at this data the first time, my gut (informed from talking with a bunch of brands about their loyalty programs) was that there’s fear around the percentage-based discount.

If a brand uses a percentage-based discount, the amount of the discount is “uncapped.” Effectively, if a customer wanted to spend enough, it could end up costing the brand a significant amount of contribution dollars. A fixed-dollar discount (like $25 off, for example), on the other hand, meant that brand is guaranteed to limit the discount.

Sure, you might overpay on the offer to convert some customers, but the amount needed to pay is known. And that level of knowing means you can bake the discount into projections with much more clarity than any percentage off deal could provide.

And, if there’s one thing a brand likes, it’s certainty in the forecast.

I think, however, there’s an underlying issue at play here: Brands aren’t quite sure how to think about the impact of their loyalty program.

If, for example, you’re not sure a loyalty program is delivering value (but you’re maybe doing it because one particular team member feels so strongly about it), then you’re probably looking to cap the discounting dollars as much as possible.

What brands often miss, though, is that loyalty is a merchandising lever. (They’re not exactly to blame. Loyalty program vendors have spent a long time telling them to look at loyalty programs in a way that was more valuable to the vendor than it was instructive in showing the true value of the program.)

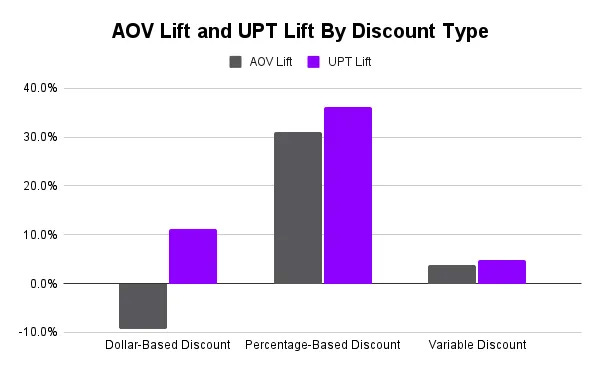

So, if you set aside the argument of whether loyalty programs drive incremental purchases, and look instead at whether loyalty programs can positively impact buying behavior when someone is ready to buy, you can begin to understand whether a different discount type moves the needle in the same way “the rule of 100” is proven to do so.

And we’ve looked at this.

Perhaps, then, the takeaway here is straightforward: your loyalty program is a merchandising lever in the same way your BFCM discount is a merchandising lever. Which one works, and what the structure of it should be to drive the best results, requires a dive into the data, some testing, and a willingness to rethink what impact your program is driving.